La Noire De...

by Ousmane Sembène

Senegal, 1966

program:

El cine después de la liberación

The film and accompanying commentary include racial slurs that are offensive and may be triggering. While Cinelogue does not condone the use of these terms, they are part of this film and speak to the colonial history of its context.

about the film

La Noire De… is considered by critics to be the first feature film directed by a Black African filmmaker*, Ousmane Sembène. The film was released in 1966 and plays out in Senegal and France. In the film, Sembène offers a novel postcolonial reading of the relationship between France and Senegal, showing, camera in hand, that the defense of the working class is what motivated his cinematic work.

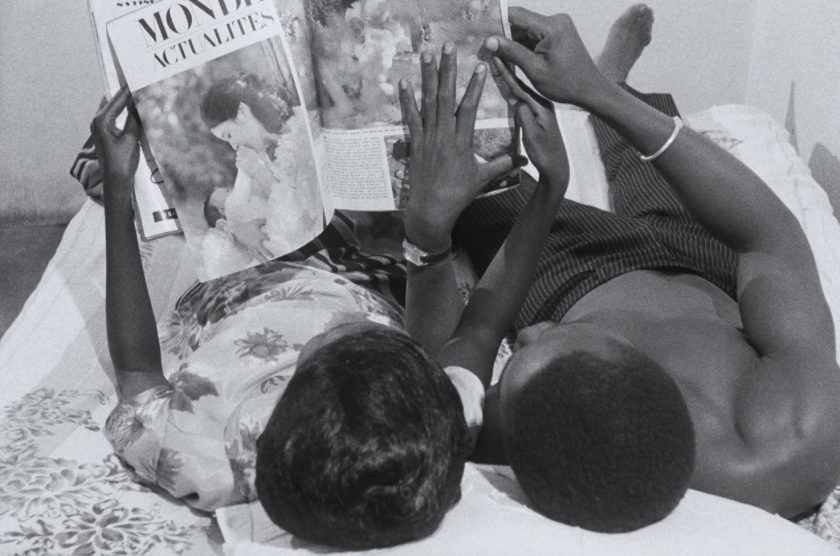

Race is a fundamental element of the film through the journey made by the protagonist Diouana as she joins her employers in France. In addition to race, there are the combined elements of class and gender. Upon her arrival in France, Diouana experiences a demotion in her social position. Diouana discovers her status as a “Black girl”** through the lustful looks she receives in France.

At the same time, La Noire De is a film built around Dakar, the capital of Senegal, a city with very strong symbolism. Due to the technical cooperation between Senegal and France, the former capital of French West Africa has become a metropolis where the majority of French people still live, even though the country is now independent.

Diouana enters the service of a French couple. Serving as a maid to “Madame”, this job carries her up the social ladder, allowing her to leave her populous neighborhood to cross the bridge separating her from the Plateau, Dakar’s central business district. Diouana crosses the bridge that separates her world from that of her bosses every day with pleasure, as it allows her to live her dream – to one day leave Senegal for France.

France, her dream destination, however, offers another, much more sinister reality than what Diouana imagined. She spins around in her new, cramped living environment like a caged animal. This new space, so small and unconducive to flourishing, is the setting for recurring conflicts between Diouana and her boss.

Sembène plays heavily on the dichotomy between the West, civilized and civilizing, and the “other”. The “other” includes all those who have not reached the threshold of modernity and civilization. His work is all the more important because, from the point of view of an (ex-)colonized person, to portray the former colony in such a raw light was audacious. At a time when new cities were being built, turning the balance of power by giving the formerly colonized a voice through cinema is in itself an inversion of the logic of power.

Diouana is a subordinate and for that reason alone she must silently endure bullying and humiliation. Diouana silences herself and resists as best she can. Until she can’t stand it anymore.

The power logics at play imply that despite the independent status of African countries, whiteness continues to be the norm and does not suffer any form of opposition. Sembène allows himself to be the voice of the voiceless and, sixty years after the release of La Noire De…, his message continues to be remarkably astute.

* “Black African” written in this text refers to a continental African person. This is the preferred wording of the author and is translated directly from the original French text.

**The original French text uses the term “négresse” to highlight the violence the main character endures by the white community in France through her intersecting identity as a black woman, specifically from a former colonized country, Senegal. The English translation “Black girl” refers to the original English title for La Noire De...

historic context

The direct European occupation of Western Africa began in the 15th century and ended when Senegal and its neighbors gained their formal independence at the turn of the 1960s. The region experienced almost 500 years of domination and exploitation by competing European powers, such as Portugal, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. France established its first colonial trading base at the mouth of Senegal in 1638 and chose Dakar as the capital of its West African colonial empire in 1870.

While formal independence did not lead to the full benefits of freedom that the people of Senegal had hoped for, it did make space for an outburst of emancipatory cultural and artistic expression.

sobre el director

Ousmane Sembène is a writer and film director from Senegal. He is regarded as one of the pioneers of African cinema, more specifically the genre of film referred to as African cinematic realism. He saw filmmaking as an extension of his political activism and used the medium to make his critique of hegemonic forces, such as colonialism, patriarchy, and capitalism.

In order to make his critique more easily accessible to a broad African audience outside of elite circles, Ousmane Sembène began his cinematic practice by turning his anti-colonial novels into short films. He was one of the first post-independence African filmmakers to use cinema and film as barrier-breaking tools to reach a wider audience.

Sembène’s artistic journey reached its peak in the early 1960’s when Senegal gained its independence from direct French colonial rule. In a time when cultural representation and artistic expression found new space to flourish, his practice offered a strong reflection of Senegal’s struggle for complete emancipation.

Sembène’s works have been banned in both Senegal and France. While many of his films focused on the crimes of French colonial rule, he was also balanced in his critique of post-independence authoritarianism, elitism, and traditional practices in Senegal that are oppressive towards women. Sembène saw women as crucial, active agents in the struggle for liberation.

about the author of this text

Ndèye Fatou Kane is a Senegalese blogger, writer and researcher. After being one of the first people in Senegal to have created a literary blog, she began writing. Her first novel Le Malheur de Vivre (The Misfortune of Living) was published in 2014. She then switched to feminist activism and gender studies. Her research first focused on Senegalese feminism and intersectionality, then on the construction of Senegalese masculinities from a politico-religious perspective.