Tajouj

by Gadalla Gubara

Sudan, 1977

program:

El cine después de la liberación

about the film

Considered the first feature film of Sudanese production, Tajouj lends itself to the epic genre, as it is adapted from a Sudanese folk tale on the values of heroism, bravery and love. The story poses questions about loyalty, betrayal, and the difficult decisions its protagonists face in the contexts of their societies and their surrounding power dynamics.

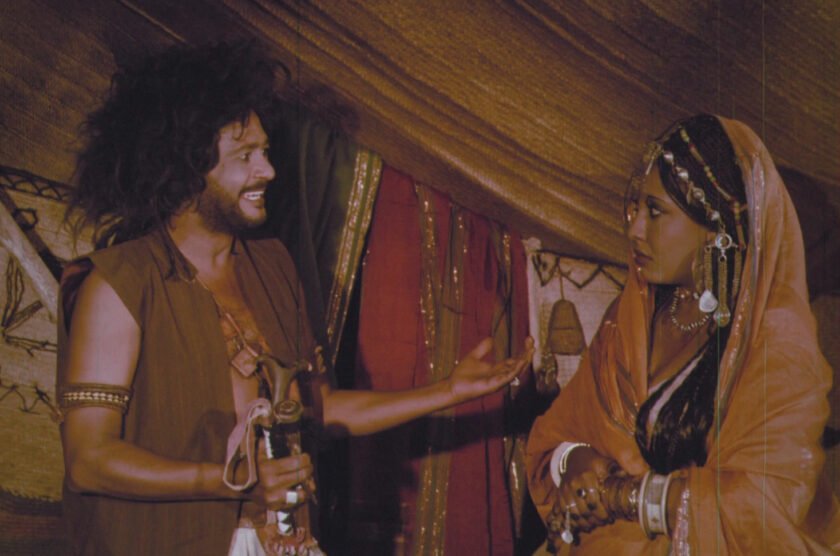

Tajouj is an impassioned 19th century love story between its beautiful namesake heroine Tajouj, played by actress Majda Hamadnalla, and her cousin Al Mahalaq—the brave knight and singing poet.

The movie weaves its strings with sorrow to create a tapestry laden with melodrama, a characteristic element of the movie strongly expressed through Gubara’s technique.

In terms of category, Tajouj can unmistakably be considered a commercial film. It fulfills the cornerstones of commercial cinema, from its ringing, rhythmic nature as a folk tale adaptation, to the casting decisions of singer Salah ibn Al Badia (1937-2019) as the handsome hero with a poignant voice, and generational sensation Majda Hamadnalla as its heroine.

The movie was shot in the eastern region of Sudan, with its bumpy terrains, rough mountains, and stretched out expanses of burning sand. It is that same Sudanese east that still suffers ferocious alienation and marginalisation in the movement of history. The eastern desert is —to this day— overlooked by the sluggish vision of development in the capital city and center Khartoum.

In spite of the commercial elements in Gubara’s film, it is also a work that holds a set of coordinates related to questions of ‘Sudanese identity’. The film is based on a story that is akin to and converses with those of Arab tradition in the Arabian peninsula, like the epic tale of Majnun Layla. According to the historical narrative, the story’s protagonists have immigrant origins from the east of the Red Sea in Yemen, so the film has an overwhelming typifying of values and morals particular to that region. Yet, this all takes place within an African environment not only in its geography, but also in the fashion and the jewellery that decorates the bodies of men and women, as well as the rituals of magic that affect the film’s path and reorient its plot direction.

On the other hand, looking at Tajouj, we perceive a work of art that transgresses politically constructed borders. Did we mention colonial borders? We find ourselves in East Sudan, the film’s center stage, where the Sudanese Shukriya tribes intermingle with the Bani Amer kin who are of genetic relation to Ethiopia, all combined with the Yemeni origins of the protagonists.

It is a geography that is brimming with ethnic interaction, and the absence of borders drawn by politics and barbed wire. There are no borders that delineate, categorise or restrict the flow of human movement.

It is the world before colonial mapping.

A world of deep-rooted human amalgamation.

When we look at Tajouj, we see a formula for cultural and human integration, and different forms of openness and fusion. We also see local tradition(s) in a way that appreciates migrations and the intermingling of different cultures, and these cultures’ ability to build a common social basis, further fortifying what we can call universal human culture.

It is perhaps then useful to be able to view a movie like Tajouj openly and around the world. It is a work that reintroduces Sudanese viewers to a part of themselves, and it can also give its world audiences a piece of Sudan’s unknown picture, a picture that is marginalised in the contexts of ‘official world history’.

Going back to Gadalla Gubara, it is important to point out this 1920-born visionary artist’s ambition to develop Sudanese cinema. He dedicated himself to it, letting go of his prestigious government job to create Studio Gad, the first film studio in Sudan where he produced Tajouj as well as a group of other works like Baraka Alsheikh and Al Bo’asaa (Les Misérables). This came after an educational journey throughout which he studied cinema and filmmaking in Cyprus, Cairo and the United States.

He then largely contributed to the presence of Sudanese films in international festivals, and to the formation of the FESPACO film festival, which has finally celebrated him this year as an in memoriam honorary guest in its 2021 round.

With all of the various political, cultural and economic transformations that have swept through Sudan, Gubara remains unknown in his country. All of these changes have negatively impacted the necessary accumulation for the building of Sudanese cinema and for revitalising it. Yet, today, we read the tale of Sudanese cinema as an impassioned romantic or folklore tale, like that of Tajouj: a tale full of heroism and hope.

awards and festivals

The film won the Nefertiti Statue at Cairo International Film Festival in 1982.

It also won prizes at film festivals in Alexandria, Ouagadougou, Tehran, Addis Ababa, Berlin, Moscow, Cannes and Carthage.

about the author of this text

Talal Afifi is a renowned Sudanese Film curator and producer, as well as director and founder of Sudan Film Factory (SFF) and president of the Sudan Independent Film Festival (SIFF).

As an influential professional within cinema culture and the film industry in Africa and the Arab World, Afifi contributed to producing more than 40 films from different genres that have found their place on the regional and international scene.

The text was translated from Arabic by Nada Nabil.